Astronomers have discovered an ancient reservoir of gas that is too hot for cosmic models to handle, reports a study published on Monday in Nature.

By peering over 12 billion years through time to the infant cosmos, a team captured an unprecedented glimpse of a baby galaxy cluster called SPT2349-56. Cosmological models suggest that the gas strewn between galaxies in these ancient clusters should be much cooler than gas observed in modern galaxies, which has been heated up by the intense gravitational interactions that play out in clusters over billions of years.

But the new observations of SPT2349-56 reveal an inexplicably hot reservoir of this intracluster gas, with temperatures similar to those at the center of the Sun, a finding that is “contrary to current theoretical expectations,” according to the new study.

“It is a massive surprise,” said Dazhi Zhou, a PhD candidate at the University of British Columbia who led the study, in a call with 404 Media. “According to our current theory, this kind of hot gas inside young galaxy clusters should still be cool and less abundant, because these baby clusters are still accumulating and gradually heating their gas.”

“This one we discover is already pretty abundant and even hotter than many mature clusters that we see today,” he added. “So, it's a bit different and forces us to rethink our current understanding of how these large structures form and evolve in the universe.”

The first stars and galaxies emerged in the universe a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, during an era called cosmic dawn. Galaxies gradually accumulated together into large clusters over time; for instance, our Milky Way galaxy is part of the Laniakea supercluster which contains about 100,000 galaxies and stretches across hundreds of millions of light years.

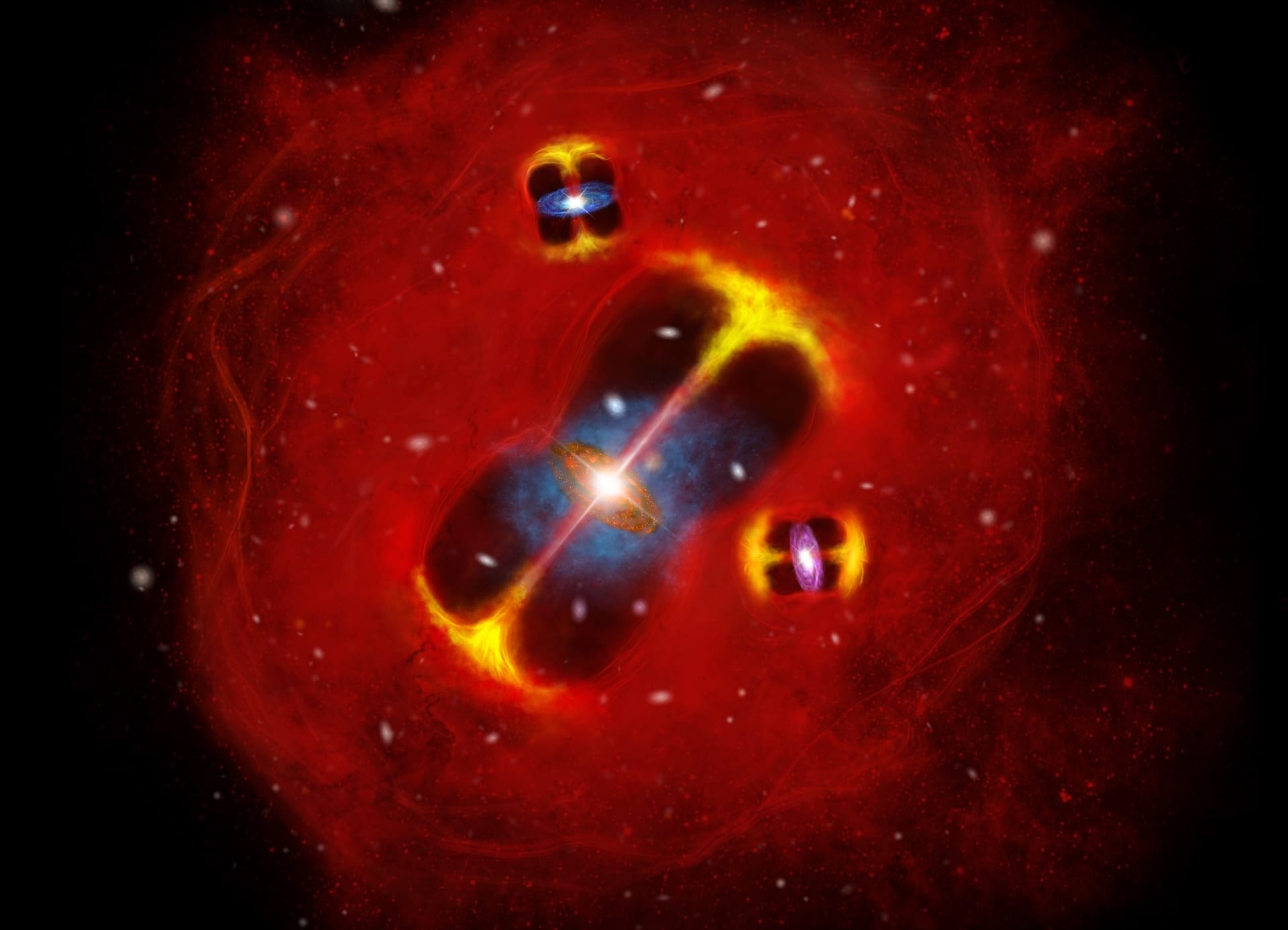

As a baby cluster, SPT2349-56 is much smaller, measuring about 500,000 light years across, and containing about 30 luminous galaxies and at least three supermassive black holes. Zhou and his colleagues observed the cluster with Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a highly sensitive network of radio telescopes in Chile, which allowed them to capture the first temp check of its intracluster gas.

“Because this gas is pretty distant, it's very challenging to see the light of the gas directly,” explained Zhou. To probe it, the team searched for what’s known as the thermal Sunyaev–Zeldovich signature, which is a detectable distortion of the oldest light in the universe as it passes through intracluster gas.

The results produced a thermal energy measurement of 1061 erg, which is about five times hotter than expected. While the heat source is still unknown, Zhou speculated that it could be caused by high levels of activity in the cluster, where stars are forming 5,000 times faster than in our own galaxy and huge energetic jets of matter spout out of galactic cores.

However, it will take more observations of these distant clusters to figure out whether the hot gas within SPT2349-56 is an aberration, or if super-hot gas is more common in early clusters than predicted.

“Like every first discovery, we have to be cautious and careful with big results,” Zhou said. “We need to test it further, with more independent observations and comparisons to other galaxy clusters at a similar time. This is what we hope that our community will do next, and we're also planning for follow up observations of other clusters to see whether there is a broader trend or if this system is an outlier.”

The new study is part of a wave of unprecedented observations of the early universe within the past few years. The James Webb Space Telescope, for example, has discovered massive galaxies much earlier in time than expected, pointing to a tantalizing gap in our knowledge about how our modern cosmos emerged from these ancient structures.

“It is starting to change our current understanding of how energetic the galaxy formation process was in such an early time,” Zhou said. “Galaxies were formed and evolved with much more violence, and were more active, more extreme, and more energetic than what we used to expect. The James Webb results are also consistent with our current discovery that these galaxies were very powerful in shaping their surroundings.”