The Baltimore Orioles should be good, but they are not good. At 15-24, they are one of the worst teams in all of Major League Baseball this season, an outcome thus far that fans, experts, and the team itself will tell you are either statistically improbable or nearing statistically impossible based on thousands upon thousands of simulations run before the season started.

Trying to figure out why this is happening is tearing the fanbase apart and has turned a large portion of them against management, which has put a huge amount of its faith, on-field strategy, and player acquisition decision making into predictive AI systems, advanced statistics, probabilistic simulations, expected value positive moves, and new-age baseball thinking in which statistical models and AI systems try to reduce human baseball players into robotic, predictable chess pieces. Teams have more or less tried to “solve” baseball like researchers try to solve games with AI. Technology has changed not just how teams play the game, but how fans like me experience it, too.

“Some of the underperformance that we’ve gotten, I hope is temporary. This is toward the extreme of outcomes,” Orioles General Manager Mike Elias said last week when asked why the team is so bad. “So far in a small sample this year, it just hasn’t worked. And then we’ve got guys that have been hitting into tough luck if you kind of look at their expected stats … we’ve got a record that is not reflective of who we believe our team is, that I don’t think anyone thought our team was.”

Embedded in these quotes are current baseball buzzwords that have taken over how teams think about their rosters, and how fans are meant to experience the game. The “extreme of outcomes” refers to whatever probabilistic statistical model the Orioles are running that suggests they should be good, even though in the real world they are bad. “Small sample” is analogous to a poker or blackjack player who is making expected value positive moves (a statistically optimal decision that may not work out in a small sample size) but is losing their money because of the statistical noise inherent within not playing for long enough (another: “markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent”); basically, the results are bad now but they shouldn’t stay that way forever. “Tough luck” is the reason for the bad performance, which can be determined via “expected stats,” which are statistical analyses of the expected outcome of any play (but crucially not the actual outcome of any play) based on how hard a ball was hit, where it was hit, the ball’s launch angle, exit velocity, defender positioning, etc. Elias has repeatedly said that the Orioles must remain “consistent with your approach” and that they should not change much of anything, because their process is good, which is what poker players say when they are repeatedly losing but believe they have made the statistically correct decision.

Before the season, a model called the Player Empirical Comparison and Optimization Test Algorithm (PECOTA), which simulates the season thousands of times before and during the season, projected that the Orioles would win 89 games; they are on pace right now to win barely 60. The PECOTA projections simulations did not show the Orioles being this bad even in its worst-case preseason simulations. A Redditor recently ran an unscientific simulation 100,000 times and estimated that there was only a 1.5 percent chance that the Orioles would be this bad.

Right now, none of this is working out for the Orioles, who in recent years have become industry darlings based on their embrace of this type of statistical thinking. The last two years the simulations have suggested the Orioles should be near the top of the league, and in the millions of simulations run for these projections they have surely won thousands of simulated World Series. But under Elias they have not even won a single real life playoff game.

Here is how the fanbase is taking this year’s underperformance:

The team has been so bad that for several days the Orioles subreddit began to talk only about the actual Baltimore Oriole bird and not the baseball team.

The Orioles’ obsession with simulations training and treating their players like robots has become a constant punchline. On the popular Orioles Hangout forums, which I have lurked on for 25 years, posters have started calling the team the “Expected Stat All Stars” but real-life losers.

The Orioles are my favorite team in the only sport I care about. I have been a daily lurker on the popular orioleshangout.com forums since my posting account was banned there in 2003 for a beef I got into in high school with the site’s owner. I listen to podcasts about the Orioles, read articles about the Orioles, and, most importantly, watch as many Orioles games as I can. I listen to the postgame press conferences, follow all of the beat reporters. When I cannot watch the game, I will follow it on MLB Gameday or will, at the least, check the score a few times then watch the highlights afterwards.

The Orioles have not won a World Series since 1983, five years before I was born. They were good in 1996 and 1997, when I was eight years old and simulated heartbreaking playoff games in my backyard pitching the ball into a pitchback rebounder as Armando Benitez blew a critical save or as Jeffrey Maier—the most hated child in DC-Baltimore Metropolitan Area—leaned over the scoreboard and fan-interfered a home run for Derek Jeter and the hated Yankees in the 1996 ALCS. They were good again from 2012-2016. Besides that, they have been laughingstocks for my entire life.

The Orioles of the late 2010s, after a very brief 2016 playoff appearance, were known for ignoring advanced statistics, the kinds made popular by the Oakland Athletics in Moneyball, which allowed a small-market team to take advantage of overlooked players who got on base at a high rate (guys with high on base percentage) and to eschew outdated strategies like sacrifice bunting to achieve great success with low payrolls. Teams like the A’s, Cleveland Guardians, Houston Astros, and Tampa Bay Rays eventually figured out that one of the only ways to compete with the New York Yankees and Los Angeles Dodgers of the world was to take advantage of players in the first few years they were in the big leagues because they had very low salaries. These teams traded their stars as they were about to get expensive and reloaded with younger players, then augmented them over time with a few veterans. I’ll gloss over the specifics because this is a tech site, not a baseball blog, but, basically the Orioles did not do that for many years and aspired to mediocrity while signing medium priced players who sucked and who did not look good by any baseball metrics. They had an aging, disinterested, widely-hated owner who eventually got very sick and turned the team over to his son, who ran the team further into the ground, sued his brother, and threatened to move the team to Nashville. It was a dark time.

The team’s philosophy, if not its results, changed overnight in November 2018, when the Orioles hired Mike Elias, who worked for the Houston Astros and had a ton of success there, and, crucially, Sig Mejdal, a former NASA biomathematician, quantitative analyst, blackjack dealer, and general math guy, to be the general manager and assistant general manager for the Orioles, respectively. The hiring of Elias and Mejdal was a triumphant day for Orioles fans, a signal that they would become an enlightened franchise who would use stats and science and general best practices to construct their rosters.

Under Elias and Mejdal, the Orioles announced that they would rebuild their franchise using a forward-thinking, analytics-based strategy for nearly everything in the organization. The team would become “data driven” and invested in “various technology tools – Edgertronic cameras, Blast motion bat sensors, Diamond Kinetic swing trackers and others. They recently entered a partnership with the 3-D biofeedback company K-Motion they hope further advances those goals,” according to MLB.com. The general strategy was that the Orioles would trade all of their players who had any value, would “tank,” for a few years (meaning, essentially, that they would lose on purpose to get high draft picks), and would rebuild the entire organizational thinking and player base to create a team that could compete year-in and year-out. Fans understood that we would suck for a few years but then would become good, and, for once in my life, the plan actually worked.

The Orioles were not the only team to do this. By now, every team in baseball is “data driven” and is obsessed with all sorts of statistics, and, more importantly, AI and computer aided biomechanics programs, offensive strategies, defensive positioning, etc. Under Elias and Mejdal, the Orioles were very bad for a few years but drafted a slew of highly-rated prospects and were unexpectedly respectable in 2022 and then unexpectedly amazing in 2023, winning a league-high 103 games. They were again good in 2024, and made the playoffs again, though they were swept out of the playoffs in both 2023 and 2024. Expectations in Baltimore went through the roof before the 2024 season when the long-hated owner sold the team to David Rubenstein, a private equity billionaire who grew up in Baltimore and who has sworn here wants the team to win.

Because of this success, the Orioles have become one of the poster children of modern baseball game theory. This is oversimplifying, but basically the Orioles drafted a bunch of identical-looking blonde guys, put them through an AI-ified offensive strategy regimen in the minor leagues, attempted to deploy statistically optimal in-game decisions spit out by a computer, and became one of the best teams in the league. (Elias and Mejdal’s draft strategy suggests that position players should be drafted instead of pitchers because pitchers get injured so often. Their bias toward drafting position players is so extreme that it has become a meme, and the Orioles have, for the last few years, had dozens of promising position players and very few pitchers. This year they have had so many pitching injuries that they sort of have no one to pitch and lost one game by the score of 24-2 and rushed back Kyle Gibson, a 37-year-old emergency signing who promptly lost to the Yankees 15-3 in his first start back).

Behind this “young core” of homegrown talent (Adley Rutschman, Gunnar Henderson, Jackson Holliday, Colton Cowser, Jordan Westburg, Heston Kjerstad, etc.), the Orioles were expected and still are expected to be perennial contenders for years to come. But they have been abysmal this year. They may very well still turn it around this year—long season, baseball fans love to say—and they will need to turn it around for me to have a bearable summer.

Mejdal’s adherence to advanced analytics and his various proprietary systems for evaluating players means that many Orioles fans call him “Sigbot,” as a term of endearment when the team is playing well and as a pejorative when it is playing poorly. Rather than sign or develop good pitchers, the Orioles famously decided to move the left field wall at Camden Yards back 30 feet and raise the wall (a move known as “Walltimore”), making it harder to hit (or give up) home runs for right handed batters. The team then signed and drafted a slew of lefties with the goal of hitting home runs onto Eutaw Street in right field. Because of platoon splits (lefties pitch better to left-handed hitters, righties to right-handed hitters), the Orioles’ lefty-heavy lineup performed poorly against lefties. So, this last offseason, the team moved the wall back in and signed a bunch of righties who historically hit left-handed pitchers well, in hopes of creating two different, totally optimized lineups against both lefties and righties (this has not worked, the Orioles have sucked against lefties this year).

Orioles fans have suggested all these changes were made because “Sigbot’s” simulations said we should. When the Orioles fail to integrate a left-handed top prospect into the lineup because their expected stats against lefties are poor, well, that’s a Sigbot decision. When manager Brandon Hyde pulls a pitcher who is performing well and the reliever blows it, they assume that it was a Sigbot decision, and that the team has essentially zero feel for the human part of the game that suggests a hot player should keep playing or that a reliever who is performing well might possibly be able to pitch more than one inning every once in a while. The Orioles have occasionally benched the much-hyped 21-year-old Jackson Holliday, who is supposed to be a generational talent, against some lefties because he is also left handed in favor of Jorge Mateo, a right-handed 29-year-old journeyman who cannot hit his way out of a wet paper bag. The fans don’t like this. Sigbot’s fault.

Fans will also argue that much of the Orioles minor league and major league coaching staff is made up of people who either did not play in the major leagues or who played poorly or briefly in the major leagues, and that the team has too many coaches—various “offensive strategy” experts, and things like this—rather than, say, experienced, hard-nosed former star players.

Baseball has always been a statistically driven sport, and the beef between old school players and analysts who care about “back of the baseball card” stats like average and home runs versus “sabermetrics” like on base percentage, WAR (wins above replacement), OAA (outs above average, a defensive stat) is mostly over. The sport has evolved so far beyond “Moneyball” that to even say “oh, like Moneyball?” when talking about advanced statistics and ways of playing the game now makes you a dinosaur who doesn’t know what they’re talking about.

The use of technology, AI simulations, probabilistic thinking, etc is not just deployed when compiling a roster, making in-game decisions, crafting a lineup, or deciding a specific strategy. It has completely changed how players train and how they play the game. Advanced biomechanics labs like Driveline Baseball use slow-motion cameras, AI simulations, and advanced sensors to retrain pitchers how to throw the baseball, teaching them new “pitch shapes” that are harder to hit, have elite “spin rates,” meaning the pitch will move in ways that are harder to hit, and how to “tunnel” different pitches, which means the pitches are thrown from the same arm slot in the same manner but move differently, making them harder to detect and therefore hit. The major leagues are now full of players who were not good, went to Driveline and used technology to retrain their body how to do something exceptionally well, and are now top players.

Batters, meanwhile, are taught to optimize for “exit velocity,” meaning they should swing hard and try to hit the ball hard. They need to make good “swing decisions,” meaning that they only swing at pitches they can hit hard in certain quadrants of the plate in specific counts. They are taught to optimize their “swing plane” for “launch angle,” meaning the ball should leave between a 10 and 35-degree angle, creating a higher likelihood of line drives and home runs. A ball hit with an optimal launch angle and exit velocity is “barreled,” which is very good for a hitter and very bad for a pitcher. Hard-hit and “barreled” balls have high xBA (expected batting average), meaning the simulations have determined that, over a large enough sample size, you are likely to be better. Countless players across the league (maybe all of them, at this point) have changed how they hit based on optimizing for expected stats.

Prospects with good raw strength and talent but a poor “hit tool” are drafted, and then the team tries to remake them in the image of the simulation. Advanced pitching machines are trained on specific pitchers’ arsenals, meaning that you can simulate hitting against that day’s starting pitcher. Players are regularly looking at iPads in the dugout after many at bats to determine if they have made good swing decisions.

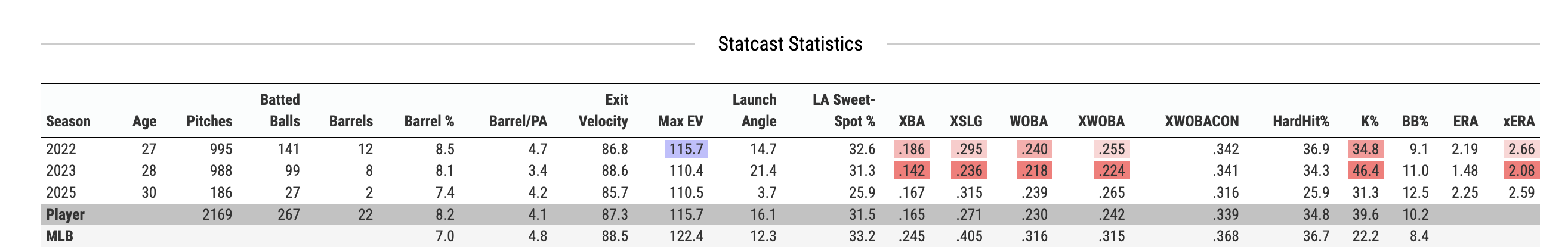

Everything that occurs on the baseball field is measured and stored on a variety of websites, including MLB’s filmroom to Baseball Savant, which is full of graphs like this:

Everything that happens on the field is then fed back into these models, which are freely available, are updated constantly, and can be used for in-game analysis discussion, message board fodder, and further simulations.

So now, the vast majority of baseball discourse, and especially discourse about the Orioles, is whether good players are actually good, and whether bad players are actually bad, or if there is some unexplained gulf between their expected stats and their actual stats, and whether that difference is explained by normal variance or something that is otherwise unaccounted for. Baseball is full of random variance, and it is a game of failure. The season is long, the best teams lose about 60 times a year, and even superstars regularly go 0-4. Expected stats are a way to determine whether a player or team’s poor results is a result of actual bad play or of statistical noise and bad luck. We are no longer discussing only what is actually happening on the field, but what the expected stats suggest should be happening on the field, according to the simulations. Over the last few years, these stats have been integrated into everything, most of all the broadcasts and the online discourse. It has changed how we experience, talk about, and should feel about a player, game, season, and team.

Rather than celebrate bright spots like when a pitcher like Tomoyuki Sugano—a softish-throwing 35-year-old Japanese pitcher the Orioles signed this year—pitches a gem, fans hop over to Baseball Savant and note that his whiff rate is only 13th percentile, his expected batting average against is 13th percentile, and his K percentage is unsustainable for good pitchers. His elite walk and chase percentage offer some hope and we should happy he played well, but they surmise based on his Baseball Savant page that he will likely regress. Fans break down the pitch shapes, movement, and velocity on closer Felix Bautista’s pitches as he returns from Tommy John (elbow) surgery, looking for signs of progression or regression, and comparing what his pitches look like today versus in 2023, when he was MLB’s best pitcher. The fact that he remains a statistically amazing and imposing pitcher even with slightly lesser stuff is celebrated in the moment but is cause for concern, because the simulations tell us to expect lesser results in the future unless his velocity ticks up from “only” 98 MPH to 99-100 MPH.

We rail against Elias’s signing of Charlie Morton, a washed-up 41-year-old who has been the worst pitcher in the entire league while collecting a whopping $15 million. The Orioles are 0-10 in games Morton has pitched and are 15-14 in games he has not pitched, meaning that in the simulated universe where we didn’t sign Morton or perhaps signed someone better we wouldn’t be in this mess at all; can we live in that reality instead? Even Morton’s expected stats are up for debate. He should merely be “pretty bad” and not “cataclysmically bad” according to his pitch charts; Morton speaks in long, philosophical paragraphs when asked about this, and says that he would have long ago retired if he felt his pitch shapes and spin rate were worse than they currently are: “It would be way easier to go, ‘You know what, I don’t have it anymore. I just don’t have the physical talent to do it anymore.’ But the problem is I do … it would be way easier if I was throwing 89-91 [mph] and my curve wasn’t spinning and my changeup wasn’t sinking and running” he said after a loss to the Twins last week. “There are just the outcomes and the results are so bad there will be times just randomly in the day I’ll think about it. I’ll think about how poorly I’ve pitched and I’ll think about how bad the results are. And honestly, it feels like it’s almost shocking to me.”

MASN, the Orioles-owned sports network, speculated that perhaps Morton’s horrible performance thus far can be boiled down to “bad luck” because of what the simulations suggest: “When these sorts of metrics are consistent with past years but the results are drastically different, we’re left with an easier takeaway to swallow: perhaps there’s nothing wrong with the pitch itself, and Morton has just run into some bad luck on the offering in a small sample size.”

Adley Rutschman, meanwhile, our franchise catcher who has been one of the least valuable players in all of Major League Baseball for nearly a calendar year, has just been unlucky because he is swinging the bat harder, has elite strike zone discipline, 98th percentile squared up percentage, and good expected stats (though absolutely dreadful actual stats). The discourse about this is all over the place, ranging from carefully considered posts about how, probabilistically, this possibly cannot last to psychological and physiological explanations that suggest he is broken forever and should be launched into the sun. On message boards, Rutschman is either due for a breakout because his expected stats are so good, or he sucks and will never get better, is possibly hiding an injury, is sad because he and his girlfriend broke up, perhaps he is not in good shape. We then note that Ryan Mountcastle’s launch angle on fastballs has declined every year since 2022, wonder if trying and failing to hit the ball over Walltimore psychologically broke him forever, and decry Heston Kjerstad’s swing decisions and lackluster bat speed, and wonder if it’s due to a concussion he had last summer. On message boards, these players—and I’m guilty of it myself—are both interchangeable robots that can be statistically represented by thousands of simulations and fragile humans who aren’t living up to their potential, are weak, have bad attitudes, are psychologically soft, etc.

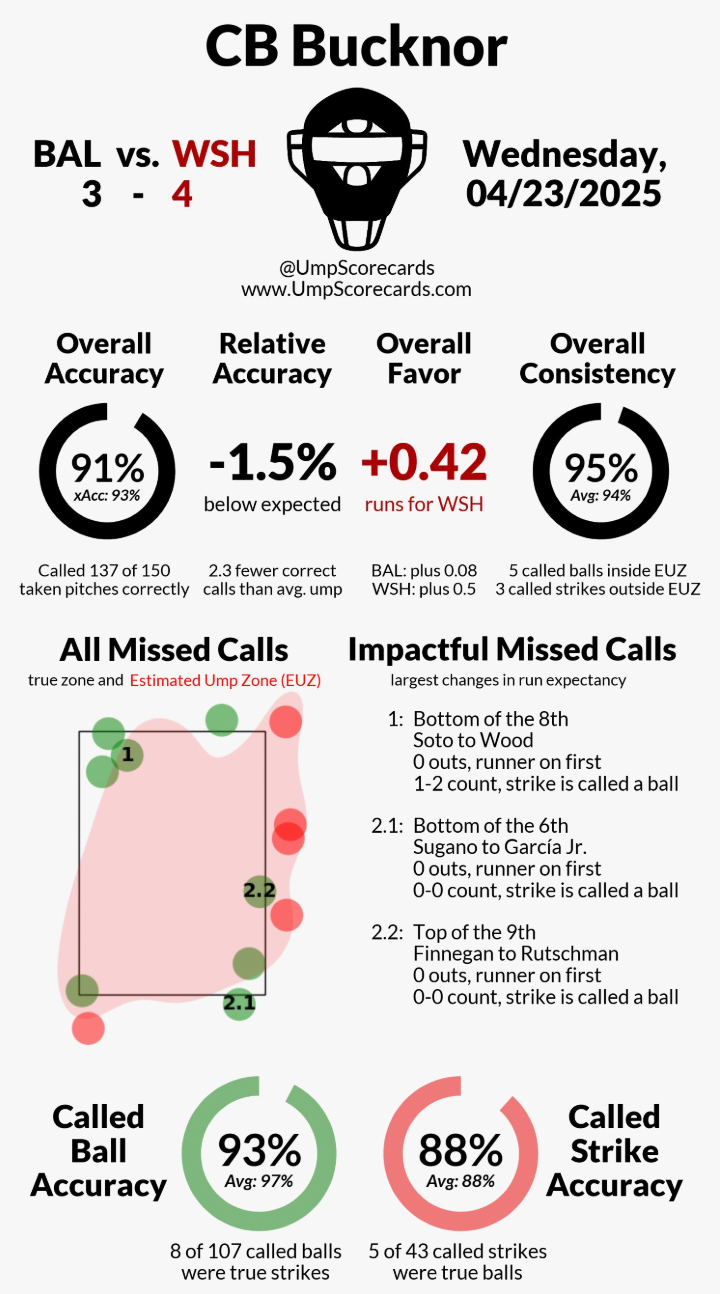

The umpires, too, are possibly at fault. Their performance is also closely analyzed, and have been biased against the Orioles more than almost any other team, leading to additional expected runs for their opponents (and sometimes real runs) and fewer for the Orioles, which are broken down every day on Umpire Scorecard. The Orioles have the second worst totFav in the league, a measure of “The sum of the Total Batter Impact for the team and Total Pitcher Impact for the team,” and a statistic that I cannot even begin to understand. If only we had that expected ball, which would lead to an expected walk, which would lead to an expected run, which would lead to an expected win, which could have happened in reality, we would have won that game.

All of this leads to discussions among fans that allow for both unprecedented levels of cope and distress. We can take solace in a good expected outcome at-bat, say the team has just been “unlucky,” or, when they win or catch a break, suggest the exact opposite. Case in point: On Sunday, Rutschman hit a popup that an Angels player lost in the sun that is caught almost every time (xBA: .020) and went for a triple. Later in the game, he crushed a ball over the center field fence that an Angels player made an amazing catch on (xBA: .510). Fans must now consider all of this when determining whether a player sucks or not, and hold it in their mental model of the player and the team. (Also, the Orioles have had a lot of injuries so far this season, which can explain a lot of the underperformance by the team but not from individual players.) This has all led to widespread calls for everyone involved to be fired, namely manager Brandon Hyde, hitting coach Cody Asche, and possibly Elias and Mejdal, too.

So, what is actually wrong?

Last August, The Athletic wrote an article called “What’s the Orioles’ secret to developing great hitters? Rival teams have theories.” The article surmised that the Orioles were optimizing for “VBA,” which is “Vertical Bat Angle,” as well as “they draft guys with present power and improve their launch angle and swing decisions … they teach better Vertical Bat Angle to reduce ground-ball rates. Swing decisions plus better VBA equals power production when those top-end exit velocities exist.” The Athletic’s article was written at a time when the Orioles’ lineup was very feared, and when Mike Elias and Sigbot were considered by many in the sport as “the smartest guys in the room.” What they had done with the Orioles and, especially, with its lineup, was the envy of everyone.

I am not a baseball reporter but I do watch tons of baseball, and this makes sense to me. What it means, essentially, is that they have been training all of their players to swing very hard, with an upward arc, and to try to swing at pitches that they think they can do damage with. This intuitively makes sense: Hitting the ball hard is good, hitting home runs is good.

But something has changed so far this year, and it’s still not clear whether we can chalk it up to injuries, random underperformance, small sample size, or the fragility of the human psyche. But so far this season, the Orioles cannot hit. They cannot hit lefties, they cannot hit with runners in scoring position, and often, they simply cannot hit at all. It is as though the game has been patched, and the Orioles are continuing to play with the old, outdated meta.

The Athletic explains that optimizing for things like VBA and swinging hard often leads to more swing-and-miss, and therefore more strikeouts. Growing up playing baseball, and watching baseball, we were taught “situational hitting,” which maybe means yes, swing for the fences if you’re ahead in the count. But also: choke up, foul pitches off, and just put the ball in play with a runner on third and less than two outs. The Orioles hitting woes this year feel like they are swinging for the fences and striking out or popping up when a simple sacrifice fly or ground ball would do; rather than fouling off close pitches with two strikes, they are making good “swing decisions” by taking pitches barely off the plate and getting rung up for strike three by fallibly human umpires, etc. Either this is random variance at the beginning of a long season, the Orioles’ players are not nearly as good as their track record and the simulations have shown them to be, or some hole in the Orioles approach has been identified and other teams are taking advantage of it and the Orioles have yet to adjust.

Bashing “analytics” has become a worn-out trope among former players and announcers, and yet, it is as though much of the Orioles team has suddenly forgotten how to hit. Watching the games, the Orioles are regularly missing or fouling off pitches thrown right down the middle and are swinging for the fences (and missing) on pitches that are well outside the strike zone. Former Oriole Mike Bordick, known for his fundamentals but not necessarily his bat, ranted on the radio the other day that this obsession with advanced pitching and hitting statistics is what he sees wrong with the team: “Charlie Morton stood there and said ‘My spin rate is better than it’s ever been, my fastball velocity is better than it’s ever been, and for some reason it’s just not working for me.’ Therein lies the problem. If we’re thinking about our spin rates and velocities, which carries over to offensive performance too,” Bordick said. “They’re chasing these [advanced analytical] numbers, and they’re not chasing competition. Putting the barrel on the ball, and throwing strikes. I mean, what are we doing? … You can’t rely on bat speed and exit velocity if you can’t put the barrel on the ball.”

Old-man-yells-at-cloud is a time-honored sports tradition, and despite writing this article, I am mostly all for the new, optimized version of baseball, as it adds a lot of strategy and thinking to a game that has always been dominated by statistics. But I am sick of losing. I do not know how to explain, when my partner asks me if the Orioles are winning or how the game is going, that “not good” actually often means “the delta between Adley Rutschman's xBA and actual BA is wildly outside the statistically expected probabilities and it’s pissing me off.” But, unless the Orioles figure out something soon, they will be one of the simulated best teams in Major League Baseball, and one of the worst teams in real life. A simulated World Series championship, unfortunately, doesn’t bring me any real-life joy.