A major mystery about a long-lost legend that was all the rage in Medieval England but survives in only one known fragment has been solved, according to a study published on Tuesday in The Review of English Studies.

Roughly 800 years ago, a legend known today as the Song of Wade was a blockbuster hit for English audiences. Mentions of the heroic character showed up in the works of Geoffrey Chaucer, for example. But the tale vanished from the literature centuries later, puzzling generations of scholars who have tried to track down its origin and intent.

Now, for the first time, researchers say they’ve deciphered its true meaning—which flies in the face of the existing interpretation.

“It is one of these really interesting and very unusual situations where we have a legend that was widely known and hugely popular throughout the Middle Ages, and then very suddenly in the middle of the 16th century, in the High Renaissance, it's just completely lost,” said James Wade, fellow in English at Girton College, University of Cambridge, who co-authored the study.

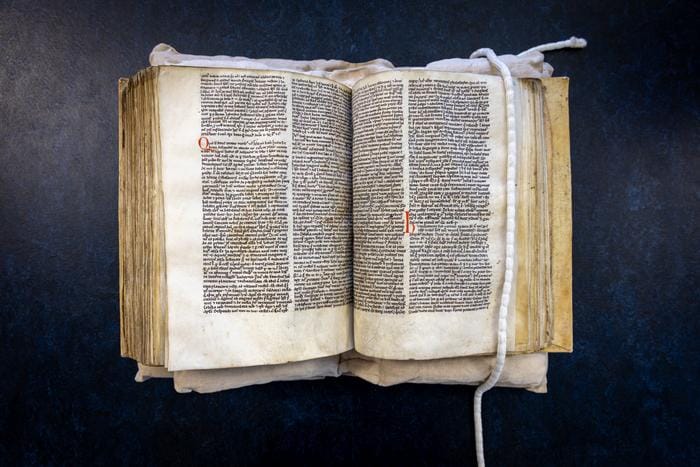

In 1896, the Medieval scholar M.R. James made a breakthrough on this literary cold case when he discovered a fragment of the Song of Wade in the Humiliamini sermon, which is part of a compendium that dates back to the 12th century. James brought the text to his colleague Israel Gollancz, a philologist with expertise in early English literature, and together they worked on a translation.

It is “the only surviving fragment” of the Song of Wade, said co-author Seb Falk, fellow in history and philosophy of science also at Girton College. “Obviously it had been around already for a while by the time this was written because it's part of the culture. The person who writes this sermon clearly expects his listeners to understand it and to know what he's talking about.”

James and Gollancz “knew there was no surviving text and they understood what they were looking at,” added Wade. “This was big news. It made the papers in 1896.”

But while the 19th century scholars recovered the sermon, their translation only deepened the mystery of the enigmatic text. For instance, references to “elves” and “sprites” in the translation suggest that the Song of Wade falls into a genre of fantastical epics about supernatural monsters. But when Chaucer references Wade in his works Troilus and Criseyde and The Merchant’s Tale, he places the character in a totally different tradition of chivalric romances which are rich with metaphors, but typically favor more grounded scenarios.

Chaucer’s mentions of Wade have perplexed scholars for centuries: in 1598, for instance, an early Chaucer editor named Thomas Speght wrote: “Concerning Wade and his [boat] called Guingelot, as also his strange exploits in the same, because the matter is long and fabulous, I passe it over.” In other words, Speght didn’t even try to decipher what Chaucer meant with his references to Wade.

This punt has become legendary in literary circles. “F. N. Robinson wrote in 1933 that Speght’s comment ‘has often been called the most exasperating note ever written on Chaucer’, and Richard Firth Green observed that Speght’s note ‘has caused generations of scholars to tear their hair out,’” Wade and Falk write in their new study.

In 1936, the scholar Jack Bennett "supposed that there is ‘probably no better known crux in Chaucer than the tale of Wade,’” the pair added.

A few years ago, Wade and Falk set out to see if they could shed light on this famous and persistent riddle. Like so many good ideas, it began over a lunchtime conversation. From there, the team slowly and methodically worked through the sermon, scrutinizing each letter and rune.

“Just trying to decipher the thing took quite a lot of work—transcribing it and then making an initial translation,” Falk said. “But I started realizing there's some really interesting material here from my point of view, as a historian of science, with lots of animals mentioned, both in Middle English and in Latin.”

As the pair worked through the text, they began to suspect that the scribe who originally copied the work may not have been very familiar with Middle English, leading to some transcription errors with certain runes. In particular, they found that the longstanding translation of “elves” and “sprites” were, in their view, more likely to be “wolves” and “sea snakes.” This transforms a key Song of Wade passage, “Some are elves and some are adders; some are sprites that dwell by waters,” to:

“Some are wolves and some are adders; some are sea-snakes that dwell by the water.”

It may seem like a subtle shift, but it is a major sea change for the interpretation of the text. The switch to animals, as opposed to supernatural beings, suggests that the preacher who wrote the sermon was using animals as metaphors for human vices and behaviors—a reading that provides a much better fit for the overall sermon, and at last explains why Chaucer viewed Wade in the tradition of chivalry.

“It became pretty clear to us that the scribe had probably made some kind of a mistake because he was used to writing Latin rather than English,” Falk said. “We're not here to say that people who read it differently previously were stupid to miss it, but I think by looking at it from the outside in, we got a different perspective.”

“It then radically changes the meaning of the passage from being about monsters to being about animals, and therefore, changes it from being a piece about mythical beasts to a piece about courtly romance,” he added.

In addition to relieving centuries-old headaches over the legend, Wade and Falk also speculate that the sermon was originally written by English poet and abbot Alexander Neckam (1157–1217), based on its style and context clues.

For the researchers, the thrill of the discovery lies not only in decoding the fragment, but in recovering a missing piece of cultural memory. While their new translation and attribution to Neckam are both tentative and may be disputed by other scholars, the study still opens a window into a long-lost legend and shows how fresh eyes can uncover insights in even the most perplexing fragments.

“By putting a completely different slant on it and, we think, understanding it properly, we have come much closer to the true meaning of the Wade legend,” Falk said. “Now, obviously we've only got three lines of this presumably much longer poem, and therefore, we can't pretend that we understand the thing in full, but I think we can understand it much better than we ever have before.”

“It reminds us that as time moves on, there's always the possibility of generational amnesia, of forgetting things, of losing things, and that when you have a chance to get a little bit back of something that humanity has lost, or that culture has lost, it's a really exciting moment,” Wade concluded.