A team of researchers from Chinese retail and technology giant Alibaba released a paper this week detailing a new model, which they call “Animate Anyone.” The reaction online to this, generally, has been “RIP TikTokers,” the suggested implication being that dancing TikTok content creators will soon be replaced by AI.

RIP TikTokers 💀 pic.twitter.com/DG5y13Dn5l

— Dreaming Tulpa 🥓👑 (@dreamingtulpa) December 2, 2023

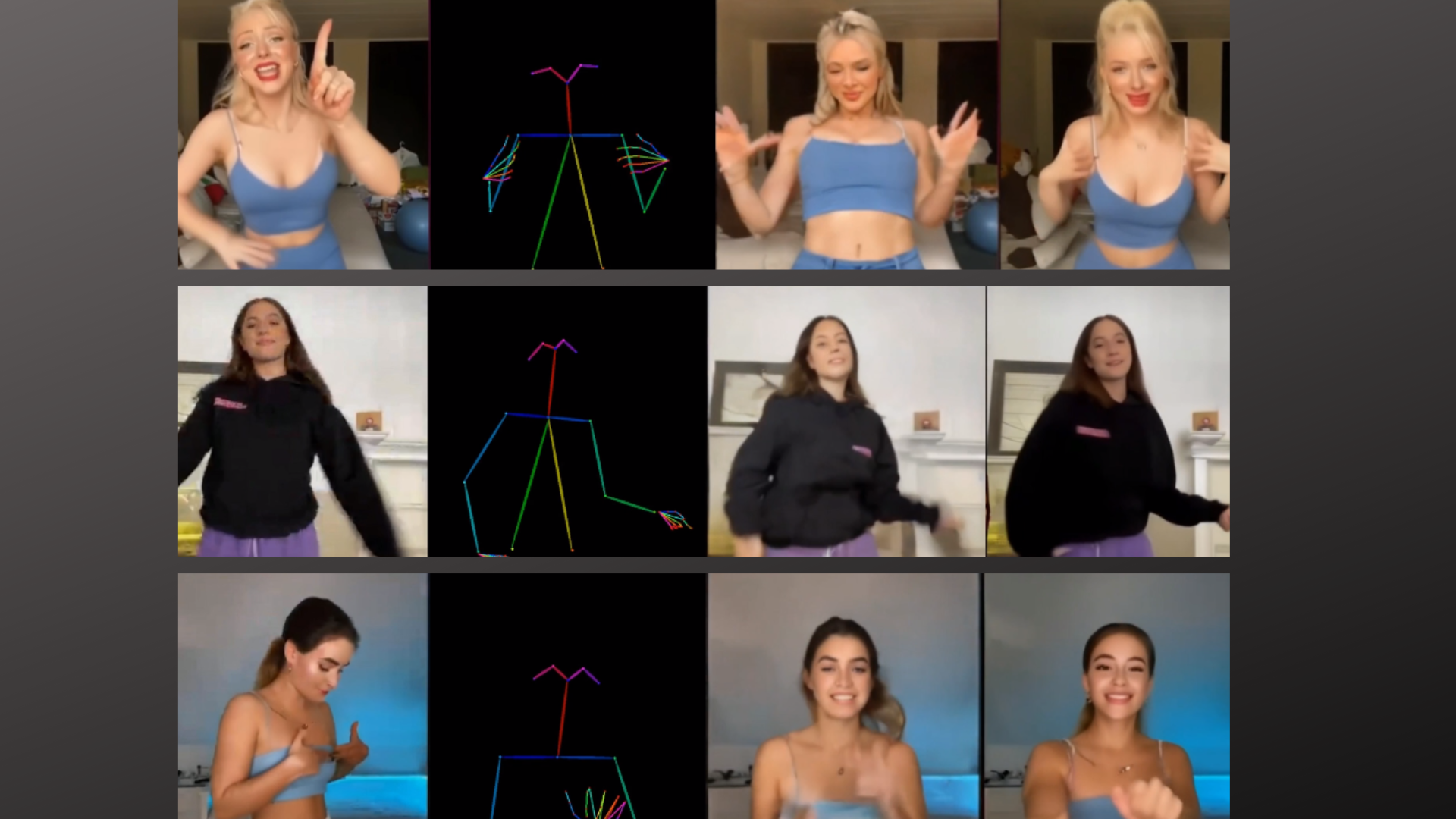

The model takes an input (in their examples, TikTok dance videos) and creates a new version as the output. The results are slightly better than previous attempts at similar models. Mostly, in the published examples, they take an existing dance sequence and replicate it slightly worse, with different clothing or styles. But as all AI advancements go, it’ll keep improving.

People have already pointed out that “Animate Anyone” will probably be used to abusive ends, generating non-consensual videos of people in fabricated situations, which has been the primary use of deepfakes since the technology’s inception six years ago.

But it’s not a far-away prediction: these researchers are already using people’s work without their consent, as a practice baked into training and building the model. The Alibaba paper is the commercialization of “the TikTok dataset,” which was originally created for academic purposes by researchers at the University of Minnesota. 404 Media’s quick look at the dataset shows that Alibaba’s new AI is trained on a model that scraped videos of some of the most famous TikTok creators, including Charli D’Amelio, Addison Rae, Ashley Nocera, Stina Kayy, and dozens of others. The TikTok dataset also contains people who have TikTok accounts that don’t have much of a following at all.

Prominent TikTok creators are featured on the Animate Anyone paper’s website as examples of the model working, where videos of popular TikTok personalities are used as the reference image, then deep-fried by the Alibaba model to grind out a worse, AI-generated replica.

This paper and the “Animate Anyone” model wouldn’t be possible without stealing from creators. The researchers use three popular online personalities and artists—Jasmine Chiswell, Mackenzie Ziegler, and Anna Šulcová—as examples in training their model on the project page.

Chiswell is a lifestyle YouTuber and TikTok personality with almost 17 million followers on TikTok. Ziegler, a singer and actress who’s known for being on Dance Moms as a child, has 23.5 million TikTok followers. Šulcová, a YouTube content creator, has 889,600 TikTok followers.

Each of these women make their living with their independent creative work, which the Alibaba team helped themselves to for its paper. There are more TikTok creators shown in the paper, published on preprint server arXiv.

The Alibaba researchers write in their paper that they use “the TikTok dataset, comprising 340 training and 100 testing single human dancing videos (10-15 seconds long).” This dataset originated with a 2021 University of Minnesota project, “Learning High Fidelity Depths of Dressed Humans by Watching Social Media Dance Videos,” which outlined a technique for “human depth estimation and human shape recovery approaches,” like putting a new outfit on someone in a video using AI.

“We manually find more than 300 dance videos that capture a single person performing dance moves from TikTok dance challenge compilations for each month, variety, type of dances, which are moderate movements that do not generate excessive motion blur,” the University of Minnesota researchers wrote. “For each video, we extract RGB images at 30 frame per second, resulting in more than 100K images.”

Most AI datasets are made up of videos, images, and text scraped from the open web, including social networks like TikTok, without the consent of the people who own that content. In this case, a dataset compiled and launched by doctoral students is being used by one of the biggest technology and retail giants in the world.

This pathway, where a giant dataset is created for the purposes of academic research then eventually becomes commercialized by large companies for similar or wholly different purposes is a common one. A researcher team at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington scraped videos uploaded by trans people to YouTube into a database that was used to create technology aimed at detecting trans people using facial recognition, for example.

AI researchers like those at Alibaba are using scraped datasets full of user-generated content in the middle of an increasingly-hostile legal environment where artists and other content creators are suing AI companies for using their works without permission. A class action lawsuit representing artists brought against Midjourney, DeviantArt, and Stability AI just added more plaintiffs and filed an amended complaint after a judge dismissed some of their claims in October. The artists claim that these AI image generators copy plaintiffs’ work, and that the generators “create substantially similar substitutes for the very works they were trained on—either specific training images, or images that imitate the trade dress of particular artists—including plaintiffs,” according to the complaint.

Last month, a federal judge overturned a decision from last year that dismissed choreographer Kyle Hanagami’s lawsuit against Epic Games. Hanagami claimed Fortnite used his dance moves as “emotes.”

“Reducing choreography to ‘poses’ would be akin to reducing music to just ‘notes.’ Choreography is, by definition, a related series of dance movements and patterns organized into a coherent whole,” the judge wrote. “The relationship between those movements and patterns, and the choreographer’s creative approach of composing and arranging them together, is what defines the work. The element of ‘poses,’ on its own, is simply not dynamic enough to capture the full range of creative expression of a choreographic work.”

Hanagami’s lawyer told Billboard that the decision to overturn the previous ruling to dismiss could be “extremely impactful for the rights of choreographers, and other creatives, in the age of short form digital media.” All of this has major implications for whatever Alibaba is trying to make with “Animate Anyone,” and academics should consider future ramifications when creating huge datasets of real people’s content.